Ghana

Tax and insurance funding for health systems

Tax and insurance funding for health systems

Prepared by Di McIntyre

Health Economics Unit, University of Cape Town

1. Overview of political, socio-economic and health context

Ghana achieved its independence from British colonial rule in 1957. It has experienced a turbulent political history since independence, with a number of coups d’etat to overthrow governments that were seen as corrupt and/or unable to effectively address the economic and social challenges facing the country. The two most recent coups (in June 1979 and December 1981) were both led by Flt. Lt. Jerry Rawlings, who on both occasions returned rule to democratically elected governments (within a few months in 1979 but only a decade later in the case of the 1981 coup). Since the 1992 elections, Ghana has had regular parliamentary and presidential elections and has experienced relative political stability since the 1981 coup.

------------------------------------------------------------------------- Macro- & socio-economic and demographic indicators ------------------------------------------------------------------------- GDP (USD 2005 Billions) 10.7 GNI per capita (USD 2005) 450 Gini coefficient (2000) 40.8 Urbanisation (% total population) 48% Literacy (% population aged 15+) 58% Population (Millions 2005) 22.1 Unemployment rate (1997) 20% ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Labour force structure by sector ( % of labour force) (2004) ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Services sector 25% Agriculture 60% Industry and manufacturing 15% ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Health sector financing/expenditure indicators (2003) ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Health expenditure, total (as a percentage of GDP) 5 Health expenditure, public (as a percentage of GDP) 1 Health expenditure, public (% of total health expenditure) 32 Health expenditure per capita ($) 16 ------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Health status indicators ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Infant mortality rate (per 1000 live births)(2004) 68 Under 5 mortality rate (per 1000 live births)(2004) 112 Maternal mortality (per 100, 000 live births)(2000) 540 Life expectancy at birth (years)(2004) 57.2 ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sources: WHO National Health Accounts website for health care financing statistics; World Bank website for all other data

Agriculture is the main economic activity in Ghana. Cash crops consist primarily of cocoa and cocoa products, which typically provide about two-thirds of export revenues, timber products, coconuts and other palm products, shea nuts and coffee. Other agricultural products exported include pineapples, cashews, and pepper. Minerals, particularly gold, diamonds, manganese ore and bauxite are also exported. Ghana's industrial base is relatively advanced compared to many other African countries. Import-substitution industries include textiles, steel (using scrap), tyres, oil refining, flour milling, beverages, tobacco, and car, truck, and bus assembly. Tourism has become one of Ghana's largest foreign income earners (ranking third in 1997).

Ghana is a low-income country with a per capita income level that is below the average for Sub-Saharan African countries. Poverty is widespread, although it has declined from 52% of the adult population being defined as poor in 1991/92 to about 40% in 1998/99. However, the incidence of poverty is unevenly distributed within Ghana, with the two northernmost regions having poverty levels of 84% and 88% in 1998/99 while Greater Accra only had a poverty level of 5%. Ghana has experienced relatively good growth levels, with GDP growth averaging 4.3% per year between 1992 and 1999, but this has not been accompanied by any improvement in the distribution of income across the population.

Although its health status indicators are slightly above average compared to the Sub-Saharan African and low-income countries averages, Ghanaians still bear a heavy burden of ill-health. Malaria is the leading cause of ill-health and premature death in Ghana, accounting for 40% of all outpatient visits and a quarter of all under-five mortality. While infectious diseases account for the major burden of ill-health, non-communicable diseases and injuries, particularly from road traffic accidents are increasing.

2. Current structure and functioning of the health system

Ghana has extremely constrained health care resources, with an estimated doctor to population ratio of 1:18,000 and nurse to population ratio of 1:1,500. The availability of staff has improved dramatically in recent years due to concerted efforts to improve health professionals’ conditions of employment. Nevertheless, Ghana has consistently been one of the countries most severely affected by international health worker migration. About 45% of the doctors and a quarter of nurses ever trained in Ghana have been lost to migration.

Ghana has both substantial public and private health sectors. There is an extensive network of about 300 mission (religious charitable) hospitals, which receive subventions from the government, some of which serve as the district hospital in areas where there is no public hospital. There are a growing number of private for-profit facilities, including an estimated 140 hospitals, 910 clinics, 108 company clinics, and nearly 400 maternity homes. It is estimated that approximately 2,400 nurse midwives, 1,400 state registered nurses, 570 medical specialists and 930 generalist doctors work in the private sector, although some of these health workers engage in dual government and private sector work. There are also a range of traditional healers and informal providers such as drug sellers.

In contrast, the public sector employs about 1,200 doctors (generalist and specialist), 420 medical assistants, 8,500 professional nurses and midwives and 5,900 enrolled nurses. In 2005, there was an estimated shortfall of over 11,000 health workers in the public sector. Public sector health services are primarily provided through hospitals (teaching, regional and district level) and clinics. The organisation of the public health sector is decentralised, with health districts carrying considerable management responsibility and teaching hospitals functioning as autonomous institutions. In addition, the Ministry of Health is only responsible for policy, monitoring and evaluation and similar functions since health service provision responsibilities were delegated to a separate organisation, the Ghana Health Service, in 1996.

There are many obstacles to health service access in Ghana, both physical and financial, particularly for the poorest. Utilisation levels are very low with about 0.5 outpatient visits to public facilities per person per year. In 1992, the poorest 20% of the population only secured 12% of the benefit of government health care expenditure while the richest 20% of the population secured 33% of the benefit of government expenditure. In an effort to promote access, Ghana introduced the Community-based Health Planning and Services (CHPS) initiative in the 1990s. Under the CHPS initiative, community health nurses serve as community resident health care providers. They are provided with a compound within the community (built with community donations of land, materials and labour), where they have residential accommodation and facilities for patient consultations. They undertake door-to-door visits to provide health education, family planning, immunisations, ante-natal care, supervised delivery, acute care services and monitor health in the community, in addition to seeing patients within their compound. An evaluation of the pilot CHPS project found that the number of health service encounters within the community increased eight-fold and improved immunisation coverage. Scaling-up the CHPS initiative was started in 1999, and there were 210 functional CHPS zones by 2005.

While the CHPS initiative appears to be addressing physical access constraints, financial access remains a serious problem in Ghana. In 2003, government and donor funding accounted for less than 32% of total health care expenditure (with quite a high dependency on donor funding), while 68% was attributable to out-of-pocket payments. User fees at public sector facilities had been abolished at independence but reintroduced in 1969. While there were initially relatively nominal fees for various health services, cost recovery fees were charged for drugs (leading to the user fee policy being termed the ‘cash and carry’ system). Although the poor are meant to be exempted from fees, very few receive exemptions in practice.

In the 1980s, a number of community-based pre-payment schemes developed in response to the access obstacles created by user fees. Some were initiated by NGOs while others by the Ministry of Health. By 2002, there were more than 159 of these schemes covering about 1% of the population. One of the oldest and most well known community-based schemes in Ghana is the Nkoranza scheme. This scheme was initiated by the mission hospital in the Nkoranza district (which is located in a rural area) and covers the fees that are charged for inpatient care. Contributions, which are collected once a year at the time of the main harvest, cover the entire family. The scheme achieved a relatively high population coverage level of 23%. While these schemes have provided financial protection against health care costs, particularly for inpatient care, for their members, the poorest households are unable to afford the contributions and so do not benefit.

More recently, the Ghanaian government has introduced a mandatory or national health insurance scheme (as described below) in an explicit attempt to provide financial protection for the entire population and move away from the ‘cash and carry’ system which was creating considerable equity concerns, largely due to the non-functional exemption mechanisms.

3. Structure and functioning of the health insurance system

In 2003, the ‘National Health Insurance Act’ was passed to operationalise the policy decision to move away from user fees and towards a pre-payment financing mechanism. The Ghanaian National Health Insurance (NHI) is designed to incorporate those in the formal and informal employment sectors in a single insurance system. The government is committed to universal coverage under the NHI, but recognises that coverage will have to be gradually extended and the aim is to achieve enrolment levels of about 60% of residents in Ghana within 10 years of starting mandatory health insurance.

The basis of the NHI system is district-wide ‘Mutual Health Insurance Schemes’ (MHIS) in each district. The NHI Act explicitly requires every Ghanaian citizen to join either a MHIS or a private mutual or commercial insurance scheme. However, government subsidies will only be provided for those belonging to a district MHIS, thus creating an incentive for people not to ‘opt out’ of the integrated NHI system by purchasing coverage through private insurance organisations. Those employed in the formal sector are covered through payroll-deducted contributions to the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) Fund (see figure below). Those outside the formal sector are expected to make direct contributions to their district MHIS, which are set at approximately $8 per adult per annum for the poor, $20 per annum for middle-income groups and $53 per annum for high-income groups. In reality, it has proved difficult to distinguish between income groups and most district MHIS are charging a single flat rate, usually set at the lowest contribution rate, which is creating sustainability concerns. Each adult in a household is expected to become a MHIS member in their own right and pay the necessary contribution, which covers themselves and dependent children under the age of 18. The National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) fully subsidises the contributions of the indigent and the elderly.

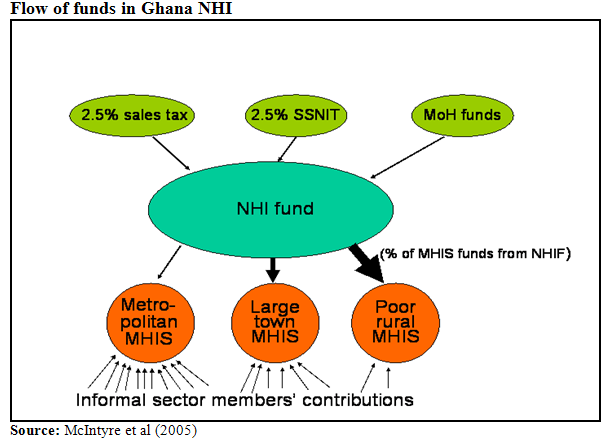

The NHIF is funded mainly by a NHI levy of 2.5% sales tax on almost all goods and services, a 2.5% payroll deduction for formal sector employees as part of their contribution to the SSNIT Fund and government allocations (including both general tax revenue and donor funding). The NHIF will allocate funds to each district MHIS in order to transfer the contributions of formal sector workers secured from the SSNIT payroll contributions, partially subsidise contributions for low-income households, fully subsidise contributions for the indigent and serve a risk equalisation and reinsurance function. The figure below attempts to illustrate how the flow of funds occurs within the NHI. It highlights that it is likely that a relatively high proportion of funds for MHIS in poor rural areas will be attributable to the NHIF, i.e. such MHIS will receive a relatively small amount of contributions from informal sector workers but large amounts of funds from the NHIF in the form of fully subsidised membershipfile:///C:/Documents and Settings/Administrator/My Documents/My Web Sites/di/images/ghana_2.png contributions for the poor.

A relatively comprehensive benefit package is provided, including general and specialist consultations, a range of inpatient services and certain oral health, eye care and maternity services. Services excluded include appliances and prostheses, cosmetic surgery, anti-retroviral treatment, fertility treatment, dialysis for chronic renal failure, organ transplants, medicines not on the essential drug list (EDL) and VIP wards. Services can be obtained from any accredited provider, which is presently restricted largely to public sector and mission facilities.

A National Health Insurance Council (NHIC) has also been established. It has wide-ranging responsibilities including: registering and regulating all insurance schemes; accrediting providers and monitoring their performance; educating the public in relation to health insurance issues; resolving complaints arising from insurance schemes, members or providers; developing policy proposals on health insurance for submission to the Minister of Health; and managing the NHIF.

While some aspects of the NHI operations are still being resolved, Ghana is moving ahead with rapid implementation of this policy initiative. By 2005, nearly 16% of the population was covered by the NHI. The distribution between different groups of contributors was as follows: 12% formal sector workers/SSNIT contributors; 16% informal sector; 20% indigents; 7% elderly (70 years and above); 1% pensioners; and 44% dependents under 18 years of age. As indicated earlier, no contributions are required for dependents under the age of 18, while most other categories of contributors (other than formal sector workers) are partially of fully subsidised by the government. The membership composition is also of sustainability concern, as most of those covered are not making health insurance contributions (indigents, dependents under 18 years etc.). Those not yet covered by the NHI continue to use public sector facilities (which receive budgets funded from general tax and donor funds) or mission facilities and pay user fees at these facilities.

4. Key issues

A number of important issues in relation to the Ghanaian NHI development should be noted. Firstly, the NHI is seen largely as an alternative financing mechanism, rather than a source of substantial additional resources. The government is anticipating devoting as much, if not more, tax revenue (and donor funds) to the health system. These funds will simply be channelled in a different way with funds gradually being redirected from the current Ministry of Health budget allocation channels to NHIF allocation channels. It is preferred to the current financing system because it will secure household contributions to health service funding (over and above tax payments) through pre-payment rather than out-of-pocket payment mechanisms. In addition, it is anticipated that exemption of the indigent will be more effective under the NHI than under the current user fee system. The main reason is that the indigent will be identified at community level in advance of needing to use a health service, in contrast to the current system of applying for an exemption at the health facility at the time of seeking care. This process will have the added benefit that health care providers will not be able to identify who is financially contributing to the district MHIS and who is not (i.e. who is fully subsidised), as all can be issued with identical insurance membership cards, which will minimise any service discrimination against the poor.

Secondly, the NHI builds on the well-established tradition of community pre-payment schemes in Ghana. As indicated earlier, there were over a hundred of these schemes in Ghana, which has ensured that many Ghanaians are familiar with health insurance principles and the operation of MHIS. However, the fate of existing community-based schemes was a major concern when the NHI was first announced. The Act clarifies that existing community-based schemes may continue to operate independently, but will not receive a subsidy from the NHIF. Attention has now turned to identifying ways of incorporating existing community-based schemes into the new district-wide MHIS (e.g. to serve as the sub-district office of the district MHIS).

Finally, there is considerable government and donor support to promote successful implementation of the NHI. The NHI was announced as an election promise and it is a promise that the government is committed to fulfilling. While many donors were initially concerned about the feasibility of such a major and ambitious health care financing restructuring initiative, they have now also committed themselves to providing all possible support for its implementation.

However, for the majority of the population who are not yet covered by the NHI, there remains a heavy burden of user fee payments and poor financial access to care.

Sources of information for case study:

- Castro-Leal F, Dayton J, Demery L, Mehra K (2000) Public social spending in Africa: Do the poor benefit? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 78(1): 66-74.

- Ghana Health Service (2006). 2005 Annual Report.

- Government of Ghana (2003) National Health Insurance Act (Act 650). Accra, Government of Ghana

- IMF and IDA (2002) Ghana: Enhanced Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative Decision Point Document. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund and the International Development Association.

- McIntyre D, Gilson L, Mutyambizi V (2005). Promoting equitable health care financing in the African context: Current challenges and future prospects. Harare: Regional Network for Equity in Health in Southern Africa. (http://www.equinetafrica.org/bibl/docs/DIS27fin.pdf)

- Ministerial Task Team (2002) Policy Framework for Establishment of Health Insurance in Ghana. Accra, Ministry of Health

- Nyonator, F. & Kutzin, J. (1999) Health for some? The effects of user fees in the Volta Region of Ghana. Health Policy and Planning, 14, 329-341

- Nyonator FK, Awoonor-Williams JK, Phillips JF, Jones TC, Miller RA (2005). The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up service delivery innovation. Health Policy and Planning 20(1): 25-34.

- Wikipedia (2006). History of Ghana. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 09:43, November 21, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=History_of_Ghana&oldid=89188705